Lincoln History

The history of Lincoln and specially selected photographs

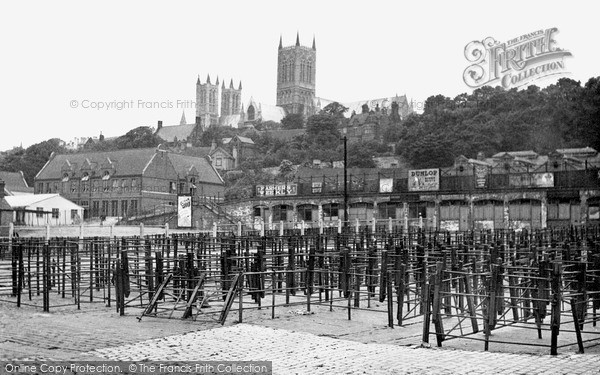

Lincoln is situated on the limestone range of hills that runs roughly north-south in the western part of Lincolnshire. Although not high in alpine terms and narrow the ridge rises to over four hundred feet where it enters the county south of Grantham and is two hundred feet high just south of Lincoln. The River Witham cuts across the ridge at Lincoln and in so doing gave the site of the city great strategic significance. This part of Lincolnshire and north to the Humber is fairly flat, apart from the rolling chalk Wolds well to the east and Lincoln Cliff as the limestone ridge is known north of Lincoln. Consequently the minster's towers can be seen for miles, from as far away as Gringley on the Hill in Nottinghamshire over twenty miles away to the north-west, from the Boston Stump thirty miles to the south-east and even from the North Sea, it is said.

However the history of Lincoln starts long before the cathedral was even thought of, for the Roman invaders after 43 AD recognised the strategic importance of the site. The Ninth Legion arrived here to cross the River Witham here around 47 AD in the invaders' steady advance from the south coast. They found a marshy river valley with a large number of shallow pools to the west, two of which survive, Swan Pool and Brayford Pool. There was earlier settlement here, but the Romans gave the city its basic form. The Roman name 'Lindum' probably derives from the British and Welsh 'llyn' or lake and we can assume the area to the west and east of the immediate limestone ridge was marshy for Roman works of drainage and control included cutting the Foss Dyke both as a trade canal to link the town with the River Trent to the west and as part of this control regime. The Romans canalised part of the River Till and turned Brayford Pool into a shipping basin as well as canalising the River Witham as far as Bardney and cutting the Sincil Dyke. Of this work the Foss Dyke and Brayford Pool remain, although the Witham has subsequently been further canalised after the 1812 Witham Act.

Of just as great importance to the present town is the layout of the Roman one. The former Roman military road, later known as the Ermine Street, utilised the limestone ridge on its route from London to Lincoln and then, after 50 AD or so, northward to York, the main Roman centre of northern Britannia. The Fosse Way, the military road that briefly formed the Roman frontier from Lincoln to Axminster in Devon, had its junction with Ermine Street near South Common, before Ermine Street crossed the Witham valley on a causeway along the course of the present St Catherine's, and the High Street, then climbing steeply up The Strait and Steep Hill back onto the ridge. The legionary fortress occupied the area of the present castle and minster and immediately north. This was laid out subsequently as the basis of the Roman walled town of 41 acres which became in 71 AD a 'colonia' or settlement for retired Roman legionaries. It thus acquired the name Lindum Colonia, subsequently in Anglo-Saxon times changing from 'Lindocolonia' to 'Lindcylene' to Lincoln.

The Roman north gate to the city still stands to this day, the Newport Arch while the lower parts of the East Gate have been excavated and are exposed in a pit alongside modern Eastgate. Parts of the wall and its course survive or have been excavated, its original southern line running roughly along the castle south boundary and immediately south of Minster Yard. However, the city proved too successful and grew downhill towards the river and the trading areas, so the walls were extended in the second century AD to enclose a further 56 acres as far as the line of Newland, Guildhall Street and Saltergate, with the famous Stonebow the new south gate's successor.

The Roman walls formed the basis of the medieval walls and of the division of the medieval city that succeeded the Roman. In effect the upper town became the outer bailey to the Norman's castle and was called The Bail with the stretch of Ermine Street that bisects it called Bailgate, 'gate' being Danish for street. The lower enclosed area became the basis for the medieval city proper, together with medieval settlement east and west of the city walls and south along High Street through the older village of Wigford to the south. The Bail area had its own leet court until 1861 and came under the jurisdiction of the constable of the castle until 1835.

After the Roman occupation of Britain ended, Anglo-Saxon settlers and the older British occupied the city. Lincoln itself may have been the capital of the Anglian kingdom of Lindsey whose royal genealogy is known but which was absorbed by the kingdom of Mercia in the seventh century AD. Lindsey was converted to Christianity by Paulinus of York in 627 AD and a stone church built which was probably the seat of the bishopric of Lindsey, although the church itself was burned down by Mercian raiders before the kingdom's conquest.

All was to change, for the Anglo-Saxon chronicle entry for 838 AD records that in Lindsey 'many men were slain by the host', that is armies of Danish raiders who crossed the North Sea in their much feared longboats. So successful were the Danes that the English had to cede all of England north-east of Watling Street to Danish rule in 886 AD, the whole area of Danish control being known as the Danelaw with those areas in what is now Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire and Derbyshire being divided up among five of the Danish armies. These areas were heavily settled by Danes and the area is now thick with Danish place names amid the Anglo-Saxon ones. The armies utilised the Roman road system for defence and each had their chief town or borough: two former Roman towns: Leicester, and Lincoln and the towns of Derby, Nottingham and Stamford. However English reconquest under King Edward the Elder by 920 AD ended the Danish rule, but Lincolnshire retained Danish institutions and laws at least until after the Norman Conquest. Lincoln was by now a wealthy trading town and one of the most important in England, with a 1086 Domesday Book population estimated at around 7,000.

All was not peaceful for long and during the reign of Ethelred the Unready Danish raiding and invasion led to Gainsborough being briefly the capital of a conquered England when Swein Forkbeard, King of Denmark, wintered there in 1013-14, indeed dying there in February 1014. In 1066 William, Duke of Normandy, invaded and defeated King Harold at the Battle of Hastings and Lincoln was about to enter a new era under Norman rule. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records under 1068 that William the Conqueror built the castle, as well as those in York and Nottingham.

The Norman arrival certainly changed the town, for the older northern sector, the first Roman walled area, was appropriated by the conqueror for his castle and the rest of this area became its outer bailey or forecourt. A third of the area within the walls was cleared, involving demolishing upwards of 166 houses, and the great castle raised. There is much Norman stonework here surviving in the core of the present walls and a visit is a crucial part of touring the city. Throughout the Middle Ages also the town walls were patched, rebuilt and repaired, ditches re-dug, only disappearing gradually after Tudor times; the gates, medieval and Roman, mostly being demolished in the eighteenth century.

More visible, however, and from further away, is the next phase of the Norman city: the Cathedral. The seat of the Anglo-Saxon see of Dorchester on Thames was moved by William to Lincoln. Remigius, who had been bishop since 1067 in return for providing a ship and twenty knights for the invasion force, claimed control of Lindsey as well the rest of the huge bishopric than ran from the Thames to the Humber, a claim hotly disputed by the Archbishops of York. However, he moved north in 1072 and immediately started work on his new cathedral. It had a giant 'westwork' which survives as the lower part of the present west end. Its original design and purpose is still controversial and historians currently suggest that it may have been a fortified rectangular bishop's palace Its three giant arched niches flanked by smaller ones survive and it is certainly a most puzzling structure. Finished by 1092, the minster church east of the west block has been replaced. Remigius' west end was however retained and altered and surmounted by towers raised by the mighty Bishop Alexander after a fire in 1141. The rest of Alexander's work was swept away by the great Gothic church that followed. This rebuild was necessitated by a spectacular earthquake in 1185 but from this tragedy one of Europe's most important medieval cathedrals emerged, initially under St Hugh of Avalon, bishop from 1186 to 1200. His eastern transept and choir survive, but his east apse was replaced by the sublime Angel Choir, mainly to house his relics and accommodate the flow of pilgrims following his canonisation. St Hugh's relics were translated amid great ceremony into the Angel Choir in 1280. The nave had been rebuilt by the 1230s and the longer cathedral of St Hugh burst through the Roman east wall.

This bald description of events does little justice to the wonderful, awe-inspiring qualities of the cathedral surmounted by its three richly crocketted towers. These were once crowned by lead clad timber spires which raised the central tower's height to an astonishing 530 feet, the highest in Europe. This blew down in 1548 but the western spires, lower of course, survived until 1807.

The cathedral close was also surrounded by walls, these being licenced by the king in 1285. Finished by 1327, some of the walls survive and two of the gateways: Exchequer Gate facing the castle and Pottergate to the east (Priory Gate is a Victorian reconstruction). There are many superb and historic buildings within the close and throughout the upper town and many in the lower town, not least the Stonebow medieval gateway and guildhall, and High Bridge carrying its timber-framed houses. However the most remarkable survivals of the earlier medieval city are the Norman house, the Jew's House and to the south, St Mary's Guildhall: rare twelfth century medieval secular stone buildings. Besides these of course there are numerous later medieval buildings, many with timber-framing either exposed or concealed within later Georgian and Victorian brick casings.

The descent from the castle and cathedral down Steep Hill and The Strait is truly memorable and when you pass through Stonebow the immensely long High Street has more treasures to offer: Anglo-Saxon church towers, a Tudor water conduit, High Bridge, the Corn Exchange are but a few. The Brayford Pool area and Broadgate offer more rewards in a city whose historic areas can be walked around in a day as a taster, but you will be back again and again. Round a corner you will come upon a historic building tucked away or upon a medieval remnant such as the old Greyfriars infirmary off Broadgate, now a museum.

The city suffered from some poor re-building in the 1960s and 1970s and the road improvements have done Broadgate and Pelham few favours. The city fathers also allowed the warehousing around Brayford Pool to be swept away, but by and large later decisions were sounder and the historic fabric of the city is now in better heart.

Further Reading

To discover the histories of other local UK places, visit our Frith History homepage.

Lincoln History in Photos

More Lincoln PhotosMore Lincoln history

What you are reading here about Lincoln are excerpts from our book Lincoln Photographic Memories by Martin Andrew, just one of our Photographic Memories books.