Ancient Stones

Published on

June 20th, 2024

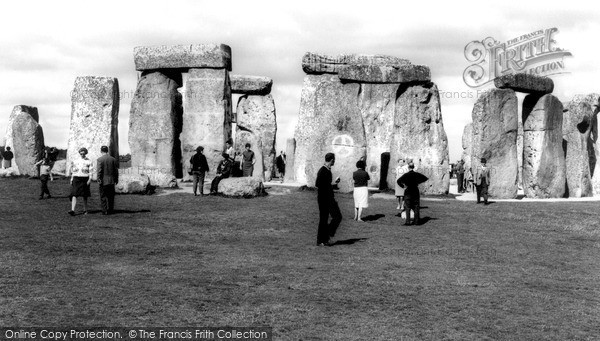

Celebrating the 20th June Solstice with photographs from The Francis Frith Collection taken at the prehistoric sites of Stonehenge and Avebury, and Glastonbury Tor and their fascinating, mystical ancient monuments and stone circles.

South Wiltshire is the location of the famous prehistoric stone circle of Stonehenge. The monument was built and adapted in three phases over a huge time span, between approximately 2,950BC and 1,600BC. The first Stonehenge was a circular bank and ditch, probably containing timber uprights, then during the second phase (2,900-2,400BC), new timber settings were erected in the north-east entrance and at the centre. During these early phases it seems the purpose of the monument was the observation of the movements of the moon through the entrance, and it may also have been linked with death and funerary rituals. The Stonehenge we see today was developed in the third phase (2,550-1,600BC). The Hele Stone and another stone west of it were erected outside the monument pointing towards the approximate point where the midsummer sun rose. Bluestone pillars brought from the Preseli mountains in Wales were erected around the Altar Stone, then came a horseshoe-shaped setting of large trilithons. Surrounding these were more bluestones, then a ring of sarsen stones. The Avenue was also constructed at this time, connecting Stonehenge with the River Avon and aligned on the point of sunrise of the summer solstice, emphasising the change of observation from the moon to the sun.

This photograph looks southwards into Stonehenge from the Hele Stone. Through the middle arch, the tallest stone of the inner horseshoe of trilithons can be seen – it is topped with the oldest tenon joint in Britain, which would have been laboriously hammered out with football-shaped flint hammers. The lintel that originally capped this stone contained the mortise to hold it in place.

Many people gather at Stonehenge each year to celebrate the summer solstice and watch the sun rise above the Hele Stone at dawn on the longest day of the year. However, at some stage rituals marking the winter solstice were also important at Stonehenge, which may have been used for ceremonies to call back the sun at the darkest time of the year. Beyond the Hele Stone, 40 posts mark the axis of moonrise at the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year, 21st December. Even all that time ago, the ancient stargazers understood that the moon’s position on the shortest day changes from year to year, over a lunar cycle of 18.61 years, and these posts marked all the positions. Four stones on the outer circle of the enclosure, known as Station Stones, also marked the intersection of lunar sight lines.

Another important prehistoric site in Wiltshire is at Avebury, west of Marlborough, which is the largest Neolithic henge monument in Britain. It was completed by about 2,600BC. Avebury’s massive bank and inner ditch encloses a circle of 98 sarsen stones, and within them were two smaller circles and a further setting of stones near the centre. (Sarsen stones are found in the nearby Marlborough downs, and are lumps of hard sandstone that were left after weather erosion of the chalk belt.) In prehistoric times there were four entrances into the henge marked by larger stones; these entrances are now used by modern roads, and some village houses at Avebury stand within the monument; these include the Red Lion pub, claimed to be the only pub in the world enclosed by a prehistoric stone circle!

One of Wiltshire’s most impressive ancient monuments is the West Kennet Long Barrow, a Neolithic chambered tomb situated just south of the A4 between Marlborough and Beckhampton, which dates back to around 3,400BC. It is around 330ft (100m) long by around 66ft (20m) wide, making it one of the longest prehistoric barrows in Britain. Excavations in the 1950s discovered the remains of between 40 to 50 people inside the barrow, which is made up of five burial chambers set laterally either side of a corridor, with the largest chamber situated at the far western end. A number of eerie tales are linked with this ancient place, but the most famous is that at dawn on the summer solstice, the ghostly figure of a man dressed in flowing white robes is said to stand on top of the eastern end of the mound, accompanied by a large hound with fiery red eyes. They stand motionless as they await the sunrise – then at first light, they turn and make their way to the entrance to the tomb, where they disappear inside….

The massive stone seen in this view stands at the south entrance into the monument at Avebury. There is a small, naturally formed, ledge on the outside of the stone (just behind the hat of the lady on the right) which can be used as a seat, hence its nickname of ‘The Devil’s Chair’.

In the Middle Ages the Church ordered that the Avebury stones were to be buried, to remove such pagan relics from the landscape. During excavation and restoration work at the ancient monument in 1938, a man’s skeleton was discovered beneath one of the buried stones. Because his remains were found with some surgical tools as well as medieval coins, it is believed that the man was probably a barber-surgeon who died around 1330 when the stone fell on him during this work. The stone (in the south-west of the circle) has now been raised again and is known as the Barber’s Stone.

Glastonbury Tor in Somerset is another popular place for people to gather to celebrate the summer solstice – and also enjoy the spectacular views from its summit, which rises 158m above the Somerset Levels. Set as it is in the Somerset Levels, the area around Glastonbury was marshy and prone to flooding until the development of modern drainage methods, and Glastonbury’s famous Tor must often have appeared as an island in winter – hence its Celtic name of ‘Ynys Witrin’, meaning ‘The Isle of Glass’, referring to its reflection in the water surrounding it. In ancient times the Tor may have been encircled by a spiralling, processional way used by priests and priestesses to reach the summit for their rituals, and it must have had a strong mystical significance in the distant past – the famous landmark of the tower on its summit is all that remains of a medieval church dedicated to St Michael, the archangel who defeated the dragon, symbolic of the Devil, showing that Christians saw the Tor as a site of great pagan significance which needed the protection of their most powerful saint.

This post has the following tags:

Memories,Places.

You may find more posts of interest within those tags.

Join the thousands who receive our regular doses of warming nostalgia!

Have our latest blog posts and archive news delivered directly to your

inbox.

Absolutely free. Unsubscribe anytime.